“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Subscribe today.

If running is an art form, pacing is the brushwork that brings it to life. When you’re first starting out, pace may be the last thing on your mind, since all you’re trying to do is get accustomed to spending time on your feet. But once you get serious about running goals, pacing becomes an essential skill to learn. There are all kinds of paces in a runner’s repertoire: recovery, easy, aerobic, lactate threshold, VO2Max, and, what we’ll be touching on today, race pace.

Simply put, race pace is the average speed that you plan on maintaining throughout a race. You want to be moving at a rate that’s near the limit of what your fitness allows, but still comfortable enough where you can sustain it for the duration of the race distance until the finish line. Go out too hard, and you may feel like you’re wading through a lactate sludge by the end. Go out too easy, and you’ll cross the finish line dissatisfied that you have too much left in the tank.

The best time to determine your race pace? Right now. Finding your race pace during training means you’ll know what it feels like come the day of the race, and won’t be caught off guard by how it feels. You never want to be guessing during the race, so calculate it ahead of time.

How? Well, you have several choices.

1. Using Past Race Times

If you’ve finished races before, whether it’s a 5K, 10K, half marathon, or marathon, then you have all the data you need to make a race pace estimation. Just calculate your mile splits and average them out, and that’s your race pace.

You can also use race equivalency calculators, which are in abundance online. These plug-and-play formulas take one distance, say you’re finishing time for a half marathon, and estimate what your marathon time should be, based on that effort.

For marathons, you can use past 5K, 10K, or half marathon race times and plug those numbers into the race equivalency calculator. For example, if you enter a half marathon time of 1:45 into the VDOT Running Calculator, you’ll receive a suggested race pace of 8:19 for a full marathon.

However, using this method requires some judgment-calling. Depending on how long ago this race was, you may have to reevaluate what’s changed since. Have you been reporting faster times in training? Do you feel stronger or more fit? Do you have an injury now that you didn’t then? All of these contribute to how your race pace might be changed, and may impact your decision to perform a new time trial (see below) or shave some time off your previous race time and go by feel alone.

2. Use The Magic Mile

We have Olympian Jeff Galloway to thank for keeping things simple with the Magic Mile. To perform this test, run a mile a little faster than your average running pace. This should be at a fast, challenging pace that you can still sustain for another 200 meters after you finish your mile. Your average pace here is your Magic Mile.

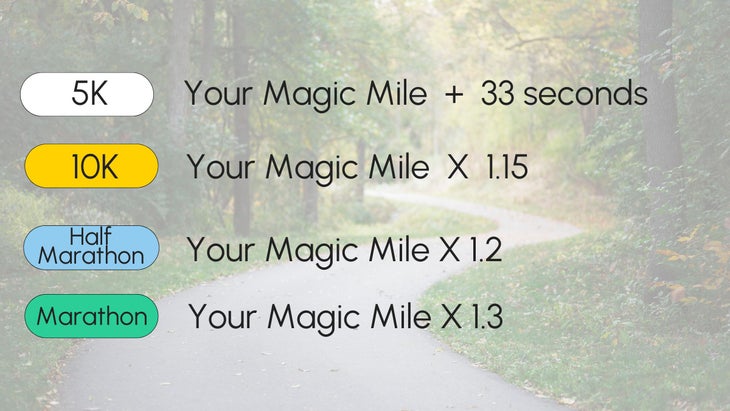

Once you have this pace, you can use Galloway’s formulas below to find your race paces:

3. Performing a Time Trial

If you don’t have any races under your belt or want a more updated, predictive race pace calculation, a time trial is an accurate means to do that. For races like a 5K or 10K, you can run one or two miles at a consistent, hard pace that you know you can keep up for the duration of that distance. For extra ease and precision, these can be run on a track. If you’re wearing a run-specific smartwatch, it will tell you your current pace throughout the run and your average pace at the end. Otherwise, you will need to divide your total time by the distance.

4. Familiarize Yourself with Training Zones

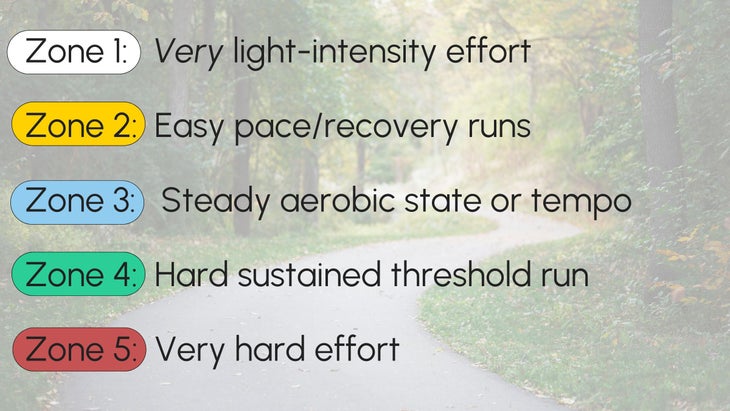

Another, more intuitive approach to finding not only race pace, but other paces essential for training, is by using your heart rate zones (or training zones). There are typically five zones a runner can fall into during their training:

To find out where your heart rate falls in these targeted zones, you first need to determine your maximum heart rate. There are a few methods you can use for this, the first being an online calculator that processes the information you input and spits out your suggested max heart rate. A common formula previously used by athletes is subtracting your age from 220, but research has shown this formula isn’t entirely accurate for everyone. The most highly recommended test is conducted by a practitioner or cardiologist, often called a treadmill stress test. But if you don’t have access to that kind of resource, you can use a chest strap monitor (for best accuracy) and perform a high intensity workout like hill intervals. Repeat the process of sprinting up the hill and walking back down, noting your heart rate at the top of the hill. By the third climb, you should have an estimate of your max heart rate.

You can plug your max heart rate into pace calculators like this one to find your target heart rate zones. Many runners find their marathon race pace is at the upper end of Zone 3, creeping into threshold pace territory, and their half marathon pace falls in Zone 4. But this is dependent on the person and distance they are running.

Which Method Should I Choose?

Matt Fitzgerald literally wrote the book on pacing, titled On Pace. Fitzgerald is a running coach of elites in Flagstaff, Arizona. He is also a nutritionist, cofounder of 80/20 Endurance, and the creator of Dream Run Camp. While there are a handful of ways to calculate race pace, he believes in using them all, if you can.

“I think it’s best to use all of them, because it’s not an exact science,” Fitzgerald says. “The more different ways you can come at it, the more reliable your estimation race pace will be.”

Jane Springston is a Denver-based running coach and the owner of Ready Set Marathon. She has a lot to say on pacing (and on the importance of strength training correctly—but that’s another story) and one of her most popular YouTube videos if an instructional lesson on How to Find Your Goal Pace (To Run Your Best Race).

Springston agrees with Fitzgerald’s premise that the more information a runner has, the better. She says that even if you have a recent race completed (recent meaning within the last six months), it never hurts to tack on a time trial. She often prescribes a 2-mile time trial to her clients because it’s long enough that she can get the information she needs without taxing a runner who might already be in the middle of a training block.

The Magic Mile is not only a good start for beginners looking to gauge their times, but it’s not too taxing on the body, so you can recover quickly.

How is Race Pace Supposed to Feel?

One of the most overlooked facets of pacing is how you should feel throughout the race.

“In our current tech-saturated environment, people forget that there’s no better source of information than your body,” Fitzgerald says. “That’s really what experienced, successful runners are doing. They know how they’re supposed to be feeling 10K into a marathon.”

If you have a good sense of what race pace feels like, you can keep coming back to that effort and reviewing the data that comes with it—like your heart rate and splits. During training, it might behoove you to practice feeling your way to the appropriate intensity of race pace without looking at your watch.

“If you truly are on the trajectory of improvement, you’ll see faster numbers with the same fixed feelings and perceptions,” Fitzgerald says.

It’s important to note that not every mile will be run at race pace. Factors like hills, elevation, terrain, and course twists and turns will force your pace to shift throughout the race. That’s why it can be beneficial to have a strategy for race day. Maybe the first half of your marathon is hilly, and therefore you start off conservatively and only pick up race pace at the back half for negative splits. Or maybe the weather forecast indicates the heat index will be high during the back half, so you start off strong and pull back later.

Point being, race pace will always be part of your racing strategy, but expecting to stay on it for the entirety of your distance isn’t always realistic or conducive to optimal performance. (And that’s especially true if your goal is to run negative splits, when the second half of your race—and the average split per mile—is faster than the first.)

How Often Should I be Training at Race Pace?

If you’re training for a specific race or goal, pacing can and should be integrated in many if not all of your runs. But you might not actually run at race pace very often. Fitzgerald recommends following a well-rounded training plan with a variety of intensities. He has his athletes perform two or three big workouts that are focused on race pace, and a handful of smaller workouts where that intensity is “touched on”.

“You need to practice at race pace, but you don’t want to overdo it,” he says. “It’s not necessary. I see a lot of runners in the 3-4 hour marathon range doing too much running at race pace.”

That being said, it’s important to remember that race pace brings about a different level of intensity for everyone. The frequency is dependent on the athlete’s level of experience and fitness.

“If I’m working with a beginner marathon runner, I don’t typically put race pace into their long runs because the number one goal at that level is to build aerobic endurance and allow the body to adapt to run longer and cover a distance they’ve never done before,” Springston says. “But they will usually be prescribed speed sessions during the week that allows them to run at race pace to allow their body and mind to know what that feels like.”

When to Recalculate Race Pace

Fitzgerald says race pace is a moving target, and thus should be re-evaluated when variables change (such as you get fitter and faster!) or time passes.

“Say you ran a marathon, took a break, and are starting with base training again,” he says. “If your goal is to improve your PR, you can start a training cycle with a provisional race pace goal, and as training unfolds, you start to get a sense of what you’re actually on track for.”

Springston suggests a little self-evaluation halfway through the training cycle.

“I think it can be helpful to prescribe a time trial mid-training cycle to check in on an athlete’s fitness to see if their race pace should be adjusted—I don’t find it necessary to do more than that in most cases,” she says. “But as a coach, I’m still recalibrating goal race pace based on other factors I’ve seen in training such as how consistent the athlete is, the volume the athlete has been able to achieve, and whether or not they are hitting prescribed paces in training.”

Can You Manipulate Your Race Pace to Meet Your Goals?

Say you calculate your race pace, and it doesn’t meet your racing goals—meaning it’s slower than what you want. What do you do then?

“You need to use your judgment. You have all this information, and you or your coach are the decision maker,” Fitzgerald says. “But your goal or ambition doesn’t change your fitness. Regardless of what your goal is, you’re only fit enough to run a certain time, so if you push it, that can be a recipe for blowing up in a marathon.”

Remember—you can always recalculate your race pace when you hit the middle of your training cycle if you really feel like you can increase your speed based on enhanced fitness. But Fitzgerald warns runners that being too attached to an unrealistic goal that doesn’t coincide with your fitness level is almost always a recipe for disaster. Going out too hard and bonking over the second half is not fun or a good strategy.

That being said, Springston has experience with changing her pacing plan on race day. In 2022, she ran the Houston Marathon and wasn’t used to the heat, so she made the decision to go out more conservatively than she planned.

“I went out about 10 seconds slower [than my planned race pace] and, even when I was supposed to up the pace at the 5K mark, I continued to stay the same pace instead because I was surprised at how much I was already sweating and didn’t want to overcook early,” she says. “Luckily, it stayed cloudy, and I was able to pick up the pace a little later. Even though I was off my goal by a couple of minutes, I still ran a strong race to get a PR and a negative split race.”

She attributes this success to making the quick decision to alter her race pace, something that can be stressful and never ideal but was necessary in that moment.

Fitzgerald says, at the end of the day, the art of race pacing is about making an informed prediction.

“You’re saying: ‘What am I capable of doing?” he says. “And that’s your goal. Not the other way around.”